From the earliest days of Spanish and Portuguese colonial rule up until the late nineteenth century, banana cultivation in the Americas was carried out mostly by smallholders. Here we trace the history of Musa sapientum, meaning “fruit of wise men,” from Southeast Asia to the Caribbean and Latin America.

Over thousands of years, humans have selected, bred, and cultivated a wide range of bananas, from green and starchy varieties for cooking to sweet and creamy varieties for eating raw. Today bananas are the most cultivated fruit crop in the world, and the fourth most valuable food crop, behind only wheat, rice, and milk. In many parts of Asia, Africa, and Latin America, bananas are a dietary staple, one that is threatened by diseases spread by commercial banana production, as Dan Koeppel has shown in Banana: The Fate of the Fruit That Changed the World (2008), a fast-moving synthesis of the scholarly literature.

As one of the cheap foods that sustain the global north, the very ubiquity of bananas leads us to take them for granted. Bananas are on nearly every kitchen table or countertop. By the end of the twentieth century, each person in the United States was consuming an average of twenty-seven pounds of bananas a year. That’s nine pounds more than the next most popular fruit, the apple.i

“They brought us . . . great quantities of pisang [the Malayan generic term for the banana], being Indian figs as large as a cucumber a span in length and of proportionate thickness, with a green rind. It is with these that our first parents should have covered them-selves in Paradise after their unfortunate Fall, because it is almost the largest and strongest leaf which one meets with in Morning and Evening lands.”ii

But five hundred years ago, there was not even a word in any European language to describe this dietary mainstay. In 1521, the chief chronicler of the Magellan expedition characterized bananas as “figs a span long” in relaying news to Europeans back home about the unknown fruit that he had encountered for the first time in Guam.iii Two hundred years later on Easter Island, Carl Friedrich Behrens called them “Indian figs” and pisang, a generic Malayan term, and analogized their size to that of cucumbers.iv In the ancient Hebrew of the Torah, the banana—and not the apple—is called the “fig of Eve.”v

In the ancient Hebrew of the Torah, the banana—and not the apple—is called the ‘fig of Eve.’

About eight to ten thousand years ago in Southeast Asia, early cultivators first domesticated bananas, developing what is believed to be the first cultivated fruit. There is both archaeological and linguistic evidence for cultivated bananas. In Papua New Guinea, archaeologists found evidence of banana cultivation dating back to 5000 BCE.vi Packed onto canoes and into satchels, dozens of varieties were diffused through South Asia, the Pacific, and Africa.

Some 2,500 years ago, Sanskrit scholars recorded the world’s first known literary references to the banana. In 327 BCE, Alexander the Great crossed the Indus and learned of bananas. Around four hundred years later, the Roman historian Pliny the Elder learned of bananas from the crews of Roman ships that crossed the Indian Ocean to trade with India.vii In India today, there are more than 670 different strains of cultivated and wild bananas.viii Muslim traders apparently brought sweet bananas from South Asia to East Africa. Gradually, banana cultivation migrated west across the continent of Africa. In the early fourteenth century, Portuguese sailors transplanted bananas to the Canary Islands. The stage was set for the banana’s journey across the Atlantic.

In 1516, the Spanish friar Tomás de Berlanga planted banana stems on the island of Hispaniola with the hope that the fruit would keep the growing slave population nourished. Easy to grow and providing a caloric punch, bananas became crucial to the colonial extraction of gold and then sugar through expropriated labor.

Or maybe bananas first reached the Americas from the Pacific. Circumstantial evidence suggests that about eight hundred years ago, Polynesian seafarers brought bananas along on their journey from the eastern Pacific to the western tip of South America.ix

Carolus Linnaeus bestowed the scientific name Musa sapientum, meaning “fruit of wise men,” upon the sweet banana after reading Pliny’s account of sages in India eating this fruit. In 1750, Linnaeus gave plantains another name, Musa paradisiaca, the “heavenly fruit,” or the forbidden fruit of paradise.x Over seven thousand years, this fruit had become the foundation of diets around the world. In North America, however, it remained unknown.

Until around 1850, bananas were not consumed in significant quantities outside of the tropics. In the Caribbean and Latin America, the descendants of slaves continued to cultivate both cooking and sweet bananas.

In 1870, a schooner captain named Lorenzo Baker purchased 160 bunches of bananas in Jamaica. With the luck of strong winds to fill his sails, he made it to Jersey City before the fruit had ripened, selling it for $2 a bunch. Initially, North Americans considered bananas to be a delicacy, an exotic tropical fruit that only the elite of the East Coast and southern port cities could afford.

Bananas are also the most widely consumed and cheapest fresh fruit in North America and Europe. But they are not native to northern climes. This discrepancy between where they are consumed and where they are produced has generated ecological, economic, and political conflicts that have shaped Central America’s relationship to the United States.

But not for long. Victorian sensibilities about the suggestive size and shape of the banana were soon overcome. As the price of bananas went down, they became more popular among the working classes in coastal cities that were connected by sailing vessels (and then steamships) to the Caribbean and Central America.

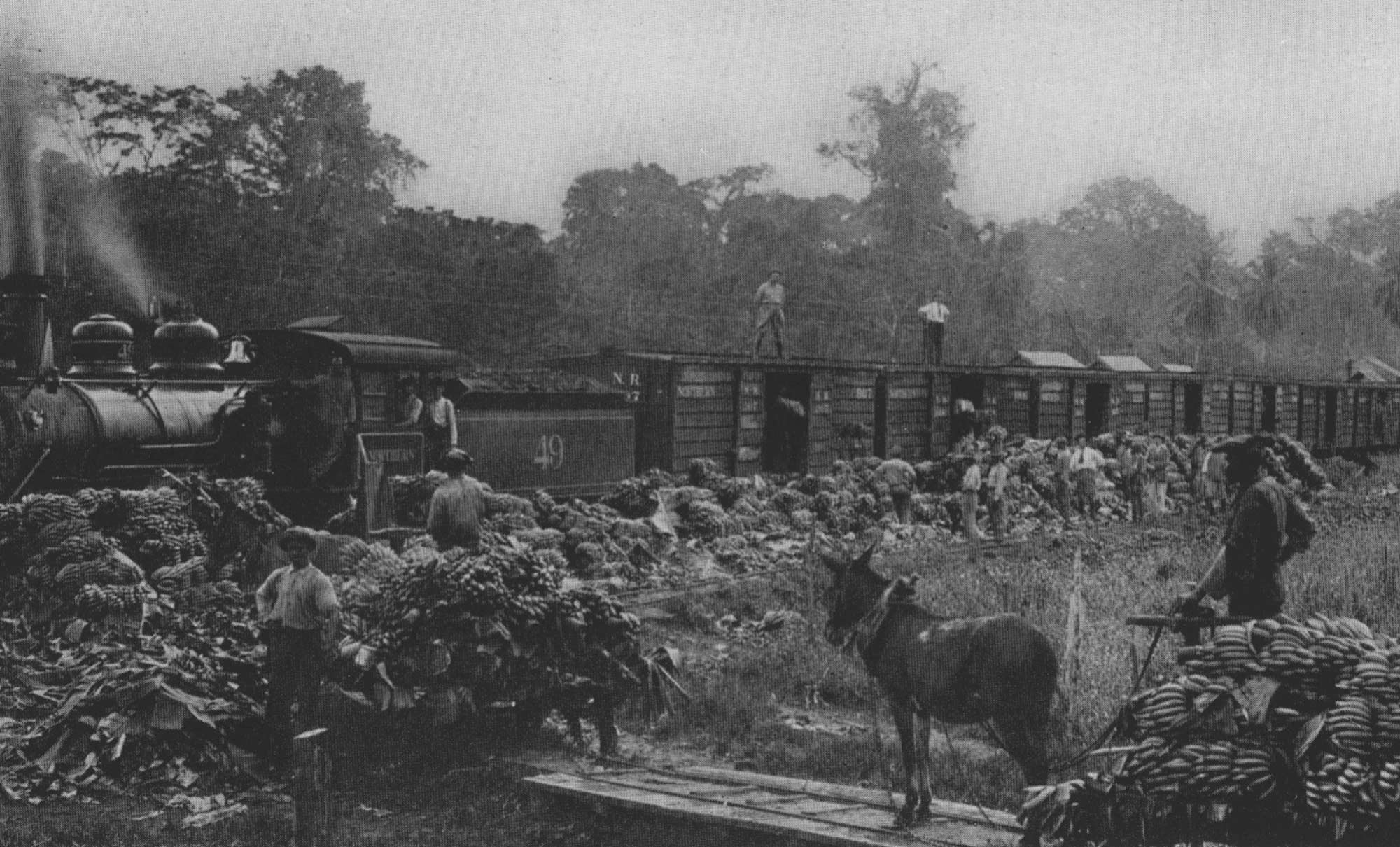

These were the golden years for local banana farmers in the region. Small producers were able to sell their fruit at reasonable prices. Buyers from the US transported, distributed, and marketed bananas, but they were not yet producing them in significant quantities. In these early years of the international banana trade, local producers had a high degree of autonomy. To this day, smallholders throughout the region plant bananas and coffee as complementary crops, one for sustenance and the other for family income.

SOURCES

REFERENCES