In 1954, the CIA overthrew the democratically elected government of Guatemala, violently reversing the progressive policies of the civilian governments. This coup was undertaken at the behest of the United Fruit Company, and it ushered in a thirty-six-year civil war that claimed the lives of approximately 200,000 civilians.

During the first sixty years of their existence, the U.S.-owned banana companies learned to use local governments as instruments of their will. From 1898 to 1920, President Manuel Estrada Cabrera invited the United Fruit Company to build Guatemala’s infrastructure: railroads, telegraph lines, and ports. General Jorge Ubico, in office from 1933 to 1944, continued to be subservient toward the company and to repress civil society.

By 1944, the balance of power began to shift in Guatemala. The initial sparks were kindled by a restive middle class. Schoolteachers went on strike, and the Ubico government responded with repression. The desire for democratic rule only spread. In July 1944, political parties were forming in Guatemala for the first free election in fifteen years. In Tiquisate on the Pacific Coast, workers for the United Fruit Company went on strike. After fifteen days, the company agreed to a 15 percent wage hike.i Ubico jailed the strike leaders. The dictatorship faced internal problems as well. A couple of junior army officers, including Jacobo Arbenz, led a rebellion at Fort Matamoros. In the ensuing battle, a total of around 1,800 loyalists and rebels died. General Ubico’s handpicked successor resigned, and Arbenz called for elections.ii

“It is to be doubted that the Guatemalan Army could ever rise, put on shoes and rush to the defense of the hemisphere or anything else without substantial U.S. support.”

In 1945, a young university professor named Juan José Arévalo assumed the presidency in Guatemala. With the ratification of a new constitution that same year, a labor law was enacted. But the landowning elite had long used the state to further their own interests above all else. The Arévalo regime found itself under constant attack, beating back one attempted coup after another. In 1947, the Ministry of Labor was established. For the first time, the state would oversee the conduct of planters. The UFCo refused to obey the new labor laws.

In 1948, Arévalo’s government arbitrated a strike on the United Fruit Company’s plantations. The company aggressively ramped up its campaign of anticommunism. The ruthlessness of the planter elite allied with the company was matched only by the increasing militancy of the newly formed labor unions. A rural laborer recalled, “I entered the union because, as a campesino worker, one needs the support of the Constitution of the Republic. We know we’re just workers, and that without that we’re worth nothing.”iii In 1950, Arévalo’s presidential term came to a close.

President Jacobo Arbenz took office in 1951. His chief concern was not that the United Fruit Company owned so much land in Guatemala, but that three-quarters of it lay fallow. The company immediately tested Arbenz by laying off 3,746 workers in its Pacific division and more than 3,000 in its Atlantic division.iv In Arbenz, agricultural workers found an ally.

After eight arduous years of workers organizing in the countryside, on June 17, 1952, Arbenz issued decree 900 to distribute land to the peasantry. This decree enabled the government to expropriate uncultivated land on any farm larger than 223 acres. The United Fruit Company had abandoned farms because of Panama disease. The government redistributed 100,000 acres, compensating former landholders based on the amount they had stated their land was worth when they filed their taxes. The UFCo had been cheating on its taxes by grossly underreporting the value of its land.

“In August 1953, the Operations Coordinating Board directed CIA to assume responsibility for operations against the Arbenz regime. Appropriate authorization was issued to permit close and prompt cooperation with the Departments of Defense, State and other Government agencies in order to support the Agency in this task.”

Back in the United States, the company hired public relations guru Edward Bernays to lead a two-pronged assault, one on the public and the other on the U.S. government.v The goal was to convince both audiences that Arbenz was a communist. Arbenz did have politicians from the Communist Party within his coalition, but the Guatemalan military remained independent. U.S. Ambassador John Emil Peurifoy pressured Arbenz to exclude all communists from legitimate political participation. The U.S. State Department intervened on behalf of the United Fruit Company, advising the Guatemalan government that it should compensate the company $16 million—what the land was actually worth, in other words, and not merely what the company had claimed it was worth to avoid paying taxes. In mid-1953, President Eisenhower authorized the CIA to overthrow Arbenz.

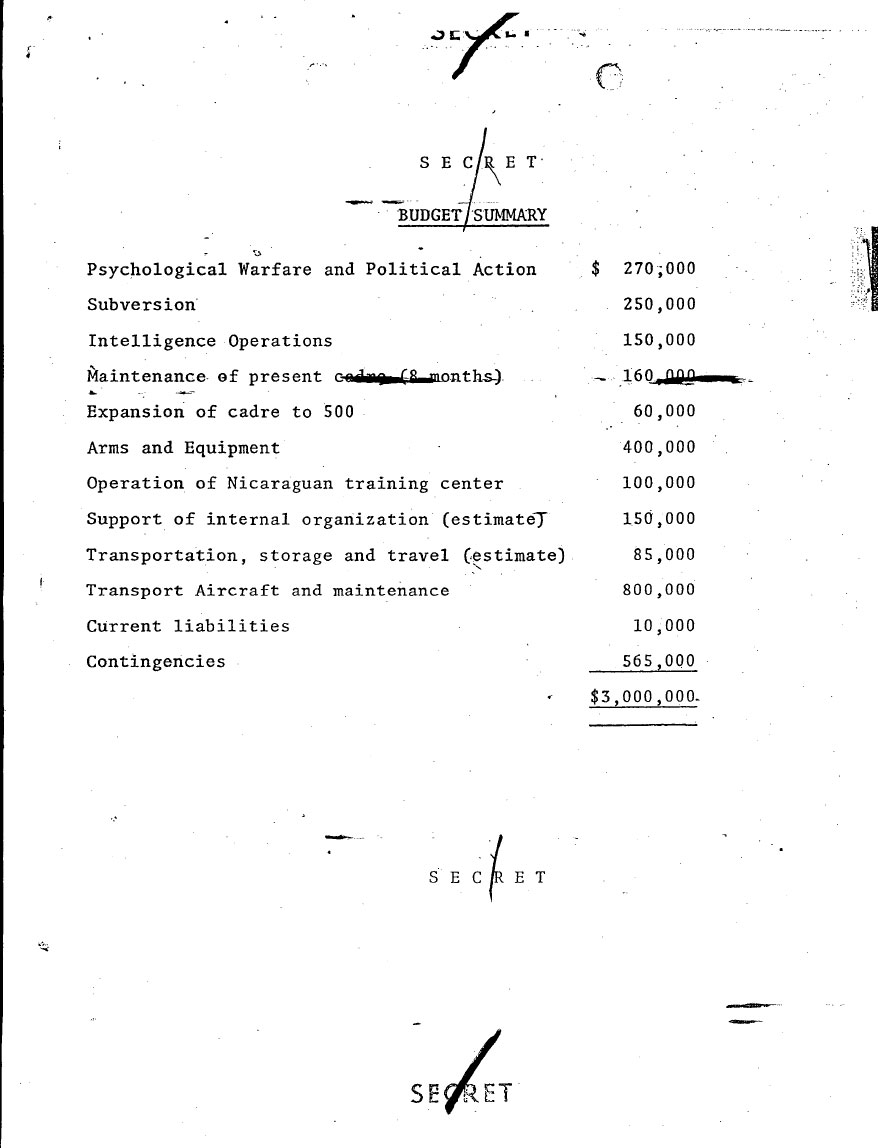

The CIA operation to destroy democracy in Guatemala was as cheap, sophisticated, and ruthless as the United Fruit Company’s cultivation of North America’s favorite fresh fruit. The heart of the campaign was psychological warfare, coupled with arming an expeditionary force out of Tegucigalpa, and a barrage of propaganda carried over the company’s Tropical Radio Network but disguised as La Voz de Liberación.

As the United States was overthrowing the democratically elected government of Guatemala, the banana workers of Honduras initiated a strike that spread across the country. The United States played things differently in Honduras, portraying the striking workers as having been manipulated by communists from Guatemala. Behind the scenes, the U.S. negotiated a bilateral military agreement with Honduras, establishing the institutional framework that would be used thirty years later to arm and train the Contras on Honduran soil.vi

“Paramilitary Operations. Approximately 85 members of the CASTILLO Armas group received training in Nicaragua. Thirty were trained in sabotage, six as shock troop leaders and 20 others as support-type personnel. The support of this operation was staged inside the borders of Honduras and Nicaragua. [ ] There were an estimated 260 men in Honduras and El Salvador for use as shock troops and specialists, outside of the training personnel that had been sent to Nicaragua.”

On June 15, 1954, U.S.-backed mercenaries left their bases in Honduras to invade Guatemala. They were led by Coronel Carlos Castillo Armas. Dockworkers for the United Fruit Company in Puerto Barrios defeated the rebels. The Guatemalan army then succeeded in driving the rebel forces back into Honduras. The invasion largely failed, but Arbenz had been shaken. Overwhelmed by bogus news manufactured in Miami radio studios, the military was paralyzed.vii Arbenz addressed the nation on the eve of being overthrown: “Our only crime consisted of decreeing our own laws and applying them to all without exception.”viii On June 27, 1954, he resigned. Immediately after the coup, UFCo workers were targeted for the worst acts of violence.

The 1954 coup ushered in a civil war that claimed the lives of 200,000 Guatemalans, tens of thousands of whom were indigenous Mayas.

LINKS

SOURCES

CREDITS

REFERENCES