Bananas and plantains are a dietary staple throughout the tropics, and the diseases that beset the Gros Michel and Cavendish varieties, which are grown on monocrop plantations, threaten a vital source of healthy and relatively cheap calories that much of the world has come to rely upon. In recent years, consumers and civil society groups have organized to demand bananas that produced in more socially and environmentally responsible ways, creating organic and “Fairtrade” alternatives to conventional “free trade” bananas.

In the early 1990s, the big three banana companies expected European unification to enable them to increase their market share. Chiquita, Dole, and Del Monte ramped up production in Latin America, cutting down more primary forests, especially in Costa Rica. But the market reforms of the European Union “did not allow banana imports to expand as expected.”i The preferential trade agreements that European countries had negotiated with their former colonies in Africa, the Caribbean, and the Pacific were effectively grandfathered in when the European Union took effect in 1993.ii

While Fyffes, Dole, and Del Monte adapted to the new regulatory environment, Chiquita did not. It lobbied the U.S. government to lodge a complaint with the World Trade Organization (WTO) and enlisted the governments of Ecuador, Guatemala, Honduras, and Mexico to sign its petition. After a back-and-forth between the United States and Europe that was dubbed the “banana wars,” the WTO ruled in 1997 that the EU banana regulations violated international free trade agreements.

But the winds were blowing against the Great White Fleet. In 2014, Chiquita merged with the Irish fruit distributor Fyffes, creating the world’s largest banana company and controlling more than one third of world banana exports. As of this writing, three companies—ChiquitaFyffes, Dole, Del Monte—control 80 percent of the global banana market.iii A number of nongovernmental organizations and civil society groups, ranging from international labor unions to environmentalists, began to develop voluntary standards that would ensure that bananas were organically and/or equitably produced. (It is possible to have one without the other: organic fruit may be harvested by child laborers, or pesticide-laden fruit may be harvested by workers who earn a living wage and enjoy the right to join a trade union.)

“The world banana market consists mainly of trade in Cavendish type bananas. The Cavendish replaced the Gros Michel as the banana entering international trade due to its resistance to Panama disease and its higher productivity (up to 60 tonnes per hectare in modern plantations). Cavendish bananas for export markets are currently produced all over the world, from small farms to large plantations of thousands of hectares.”

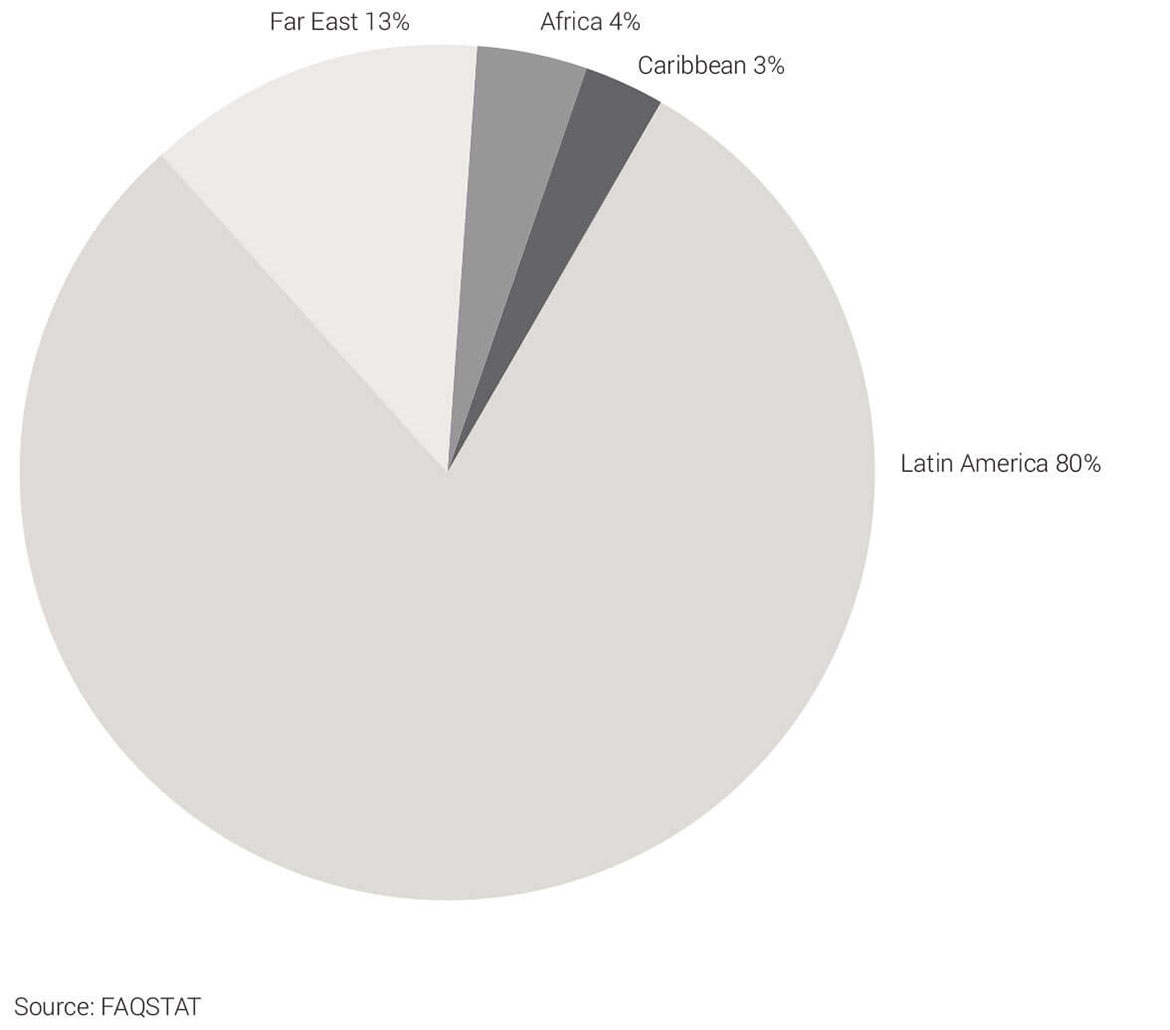

Latin America currently produces 80 percent of the bananas traded internationally. The bulk of these are grown on plantations, making a sustainable transition to organics difficult for growers of the Cavendish variety, which is highly susceptible to Black Sigatoka and crown rot. Cutting more primary forests to impede the spread of the fungus enables the (temporary) production of monocrop organic bananas. But Black Sigatoka is now everywhere, and it is increasingly developing resistance to the chemical cocktails that have been helping to keep it in check. A shift to small- and medium-scale intercropping is the best solution for growing organic bananas that won’t expose workers and ecosystems to the toxic infrastructures of industrial banana production.iv

Concern about the livelihoods and health of banana workers and their communities have led to the adoption of national labor laws and appeals to the conventions of the International Labour Organization (ILO). But the big companies continued through the late 1990s to violate those laws at will. In 2019, a massive civil suit was moving through U.S. courts against more than a dozen corporations, including Chiquita Brands International, Del Monte Fresh Produce, Dole Food, Dow Chemical, and Shell Oil, filed on behalf of banana workers who had been exposed to DBCP, a chemical that causes cancer and sterility. DBCP has been banned by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency since 1979. However, the banana companies continued to use it as a fumigant on their plantations throughout Latin America without providing their workers with gloves, suits, or respiratory equipment.v

“Fairtrade” certification provides a way for consumers to buy bananas that have been sourced in a socially responsible way, ensuring that the workers who grow, cut, sort, and box the fruit are earning a living wage. A portion of the premium paid goes directly to the producers’ community, providing a regular stream of funds to invest in education, healthcare, housing, and other cooperatively organized social programs.

The problem with both the organic and Fairtrade solutions is that they are voluntary. But because these two mechanisms rely on independent third parties to certify that producers are meeting the requirements, the extra stickers on the fruit are more meaningful than “corporate responsibility” statements, which often amount to public relations campaigns that make claims that cannot be independently verified. Production of organic and Fairtrade bananas continues to exceed demand. As consumers we should choose bananas that are in fact more ethically sourced than conventional bananas. But to get to the root of the problem, as citizens we must act to bring about the socially and environmentally responsible production and consumption of bananas. We could use our power as citizens to lobby our governments to meaningfully regulate and enforce laws that will factor in the true costs—to ecosystems, workers and their communities, and entire Central American nations—of banana production and consumption.

“Approximately 26 percent of the total Cavendish crop is exported, and 8 out of 10 bananas exported originate from Latin America. The three leading countries are Ecuador, Costa Rica and Colombia. In Asia the main exporter is the Philippines, in Africa Cameroon and Côte d’Ivoire and in the Caribbean the Dominican Republic and the Windward Islands.”

LINKS

SOURCES

REFERENCES